Ten…

Nine…

Eight…

So I had a shotgun to my head and my finger on the trigger and my lips mouthing the most ghastly countdown I’d ever witnessed in my life. What had happened? I had no idea. All I knew was that I was all alone in this ancient music hall, the old stage lying in ruins across the front five rows of moth-eaten seats that were barely visible under the rubble and the sawdust, a single dying-out electric bulb hanging from the dilapidated ceiling near the barricaded entrance, splaying a pathetic hollow yellow haze all over the place.

*****************

Perhaps it all started with that old woman in the coffee shop. The old wrinkled dark-skinned woman in the heavy brass jewelry, with the awful peeling-off make-up and the foul-smelling mug of what she called coffee and what she was trying to coax me into accepting for the whole dollar (daylight robbery in the first place) I’d spent. Oh, and her weird black hat, shaped like a bird’s nest and made like a deflated balloon or something.

She bent over me like one of Macbeth’s witches, silver-gray hair spilling out from behind one wrinkled dirty ear and took the coffee mug away from under my nose – where it had been creating a near-asphyxiation effect. Breathing a sigh of relief I was about to leap out of my uncomfortable chair and dash out of the door like a sprinter at the crucial start of a marathon, when the woman stretched one parched hand out from under her shawl and, pushing me back into my seat, whispered impishly into my ear (although it had seemed more of a cackle than a whisper at that time), “It begins today.”

So what had begun that day? Truth be told, I still don’t know. Perhaps she had meant the car that had stopped by me on the road just outside the shop and thrown out something that inexplicably smelt, looked and tasted like washing soda all over me. Perhaps she had meant the flock of white and gray birds that had alighted from the hedge around my garden, leaving behind their unwelcome leftovers all over my carefully mowed lawn. Perhaps she had meant the friendless old man who had collapsed with a heat stroke in front of my drive and made me drive him over to the nearest hospital and spend all but every cent of my money on him for a check-up and a treatment and wait for the doctor’s report plus the police report after that for six hours in that wretched stark white crowded waiting room in the crux of the afternoon. Perhaps, I hope not, though, she had meant that pretty lady in the Mercedes, who looked somewhat familiar and who’d leaned out of her window to blow a kiss at me and then disappeared behind a shaded glass.

*******************

Seven…

Six…

Five…

Or maybe the story had really started ten years ago. Under the scorching sun of the heart of Africa – a clearing in the depths of a forbidden jungle – the tall broad branches of the huge unyielding trees that hardly obstructed the glaring merciless sun, the incessant chatter of the birds and the monkeys interrupted to a standstill by the sudden gunshot that had blasted through the din, sounding like a scream in a room filled with humming priests.

I had two bullets left. My revolver was getting heavier instead of lighter in my left hand as I ran in and out through the stout trunks, creepers clinging on to the peeling bark, although the bullets kept disappearing by the minute. I heard the soft whimper of the monster behind me, its paws falling softly and surely on the thick entangled undergrowth. I was fast – but not fast enough. Not even close to fast enough for escaping a creature bred and raised in the midst of the jungle, in a race for life that was taking place in the middle of its own element, with me carrying nothing but a measly little revolver that had two bullets left only.

It was playing with me. I could sense the tense excited delight in its every footfall, movement and hot breath that escaped through its snarling display of sharp teeth – built for tearing flesh – my flesh at that.

Perhaps I lost my head back then. Perhaps it was a calculated movement on my part. Whatever it was, I left the suffocating jungle and ran into the clearing. Had I seen the abandoned temple from between the trees that bordered the clearing? I didn’t think so. However it was, with whatever fortunate twist of fate that had brought me there, there it was: an old half-collapsed temple, its northern wall a crumbling heap of dry ancient ruins, blades of new grass peeping out from between the edges of the decaying bricks.

I ran into the ruins, as far in as I could go. The animal couldn’t come in. Its huge tawny body was too large by far for the small entrance. It paced outside the doorway, an angry snarl stretching the corners of its lips, losing its temper now and then and hurtling itself at the old good wall, only to bounce back with a painful rib with each failed attempt. Its eyes were transfixed on mine, hypnotizing and unmoving, challenging and frightening, large and bright orange, the pupil a small but deep black hole, surrounded by red-green flecks. I took aim and shot the thing. The bullet whistled into the bushes behind the animal, which leapt aside with an angry growl. I could see the blood seeping out through the tough skin on his foreleg – where my last bullet had hit its mark, a foot too low for my liking.

The last bullet.

I don’t know how long I waited for a good shot. Hours, ages, maybe the whole day. When I finally lost my nerves and took aim for the shot, knowing that one bullet wasn’t enough, knowing I was going to die, the shot never rang through the thick fruit-scented air of the evening. A single arrow whizzed over my head and embedded itself in the animal’s hide. It lunged forward; the arrow seemed like an ant on its great strong muscular back for a moment; then it fell, floundering, at the foot of the wall. Poisoned.

I swerved around on my heels. A man stood in the distance, visible through a small gap in the part of the wall that had fallen in, a white man with a grin on his face. He walked around the ruins, to the entrance – where the huge beast lay sprawled across the doorway, its once terrifying eyes sightless and dazed, its tail sill thrashing the earth, raising pathetic amounts of red dust, at long intervals that got longer by the second, its breath short, slow and irregular emissions from its flaring nostrils.

The man was tall, scrawny and young. His beard, though, was white and unkempt – as unkempt as his hair was tidy. His clothes were native. He stepped over the beast and walked into the temple, towards me.

“Dr. Livingston, I presume,” I quoted, stammering, gaping, at my rescuer. His grin broadened.

“Close, Stanley,” he retaliated, his accent stiff and British, his tone friendly and informal. “It’s Daniel Scarridge to you. Dr. Dan. I’ve been working with the tribes around here for ages. Glad to be of assistance.”

“Ralph Summers.” I stretched out my hand, not even trying to lie about what I was doing, running from an overgrown wildcat in the middle of nowhere with only a revolver in my hand.

He grasped my outstretched hand in a strong grip and smiled, nodding. Then, suddenly, he snatched his hand away, his grin fading into a look of horror. He grabbed my wrist, flicked my palm over to face the sky, and scanned it intently. Then he backed away from me, his intense blue eyes probing into mine for a long moment, before turning and running towards the trees.

I called back after him. “What’s wrong?” The monkeys were chattering again, in rhythm with the twittering of the birds, at the setting in of dusk.

He paused. Then, hesitantly, he looked back. “So it hasn’t begun yet?”

I shook my head in a gesture of bewilderment. “What do you mean?”

He shrugged, crossing himself with a trembling right hand. “You’ve been marked.” It was hardly more than a whisper – but I heard it clearly in spite of the evening sounds of the jungle. At that moment all other sounds seemed to freeze into a sudden nerve-wracking eerie silence. Then the moment passed. Dr. Dan turned his back towards me and ran into the woods.

The animal gave one last jerk and relapsed into a dead stillness.

***************

Four…

Three…

Or maybe it had started that cold September night on that miserable little ship somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic fifteen years ago, the gusty wind screaming at the cabin windows and the tumultuous waves roaring as they hit the weakening hull, time and time again. The world was a chaotic mess of blue paint, dabbed randomly across a gray-black canvas, the brushstrokes strong and terrifying. White streaks of lightning slashed across the stormy skies, which growled in anger as the sea answered back with its relentless rumble.

I stood on the deck, swaying with the movement of the boat, the wind slamming into my face.

“Mr. Summers?” The voice was high-pitched, shrill almost – a small girl’s voice.

I turned. She stood by the door of one of the cabins, hardly four and a half feet tall, about eleven or twelve years old. She was muffled in a big woollen coat, sheltering her slight figure from the harsh weather. Her light brown curls fell over her cheeks, reddened by the cold. Her eyes were a clear emerald green.

“Yes?”

“He won’t wake. Mr. Reynolds won’t wake.” She was agitated, confused, shifting her weight from one foot to another.

I ran up to the cabin door and, turning the knob, pushed it open. The man sat back in his chair in one corner, staring up at the ceiling, an expression of painful surprise on his aged face, his bald head shining incongruously in the white electric light.

I bent over him and checked his pulse. Stone dead. I turned to face the little girl. “What were you here for?”

She shrugged. “I came to see if he needed something. Mary does it everyday. She’s sick today. Papa asked me.”

Mary was the stewardess and papa was the captain. I nodded. “Go call your papa. And Dr. Frisch. Hurry.”

I heard her footsteps run up the deck to the captain’s cabin and leapt to my feet. Reynolds’ glass was on the table by the chair, the rim glistening silver and the contents sparkling red. I picked it up, hurriedly, and, running out of the cabin, threw the liquid out into the sea. Then I ran back into the room and washed it carefully, meticulously, with water from the wash-stand and placed it back on the table. Then I turned around to face the dead man and smiled.

“What if tell them that the glass was full when I saw it before?”

I jumped. The girl was standing at the doorway, her hands in her coat-pockets, a complacent smile playing at the corners of her lips. I stood staring at her wordlessly, tense and apprehensive.

“You poisoned the wine, didn’t you?” She walked in calmly and sat waiting on the bed. “I saw you washing the glass.” She leaned back, resting her weight on her palms, her arms stretched back behind her. Her gaze travelled around the cabin, coming to rest on a large brown leather case in a corner.

“What’s there in that?”

I sat down beside her on the bed and shrugged the question off. “What are you going to do about it?”

She smiled again. “Are you going to kill me now because I know you did it? Don’t worry. I haven’t called papa yet. And I’m not going to tell anyone. You should know.”

I nodded. “You should call them now.”

She stood up and looked at me. “They won’t know. Don’t worry. You used a good poison.” She ran to the door and stopped to look back at me before she walked on.

“Be careful. Someday your luck will run out… and then it will begin.”

***********************

Two…

It was a warm summer night. I was fifteen. And reckless. And daring. And there was a circus camped behind our country house. So I slipped out through the kitchen door and jumped over the boundary fence and slinked towards the caravans…

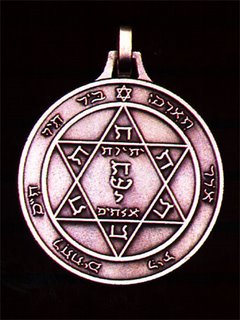

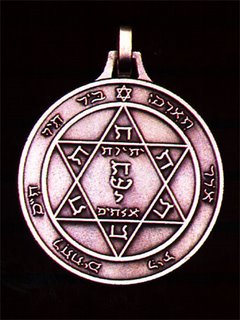

The moon slipped in and out of wispy pink-gray clouds, the sprawling green meadows splashed with silver and shadows. The caravans and the tents loomed up ahead, their vibrant colours faded into a dull gray in the light of the moon. I tiptoed up to a shaky temporary wooden stall that sold charms in the daytime. A single piece rested in the small coffee-stained glass case I’d seen on my first and officially only visit. Its silver gleamed in the moonlight streaming onto it through the old glass; the amulet was enchanting, breathtaking, even in the dark when the intricate designs on its disc were invisible. I hadn’t been able to take my eyes off it that morning. And it wasn’t for sale.

I wanted it. I wanted that old fake silver locket that hid behind a dusty corner of the shredded velvet in the showcase. I didn’t even think about the fact that all the other trinkets had been taken inside for safety and this one had been left behind; I didn’t even realize that this was too easy. I didn’t think of it as dangling bait on a fishing hook, I thought of it as luck…and I guess I was right. Too damn right for my own good.

I prised the glass open, slipping my hand in under the brass-lined cover and drew the thing out. I didn’t risk a peek at it. I turned and ran.

A branch cracked behind me. I stopped dead. And all of a sudden, in the dead silence of the still night, someone laughed. A mocking triumphant hoarse laugh, that crept into my blood and made the warm night so much colder, so much more sinister.

I turned. A figure stood poised by a caravan, against a starlit sky and the pale ghostly disc of the moon, his face in the shadows.

“It’s yours now!” His voice was guttural, his expression mocking, triumphant, excited. “We couldn’t give it to anyone, we couldn’t sell it to anyone. And now it’s yours. You’ve brought it upon yourself, boy, voluntarily. We’re free.”

I shivered, every instinct in my body urging me to run; but I couldn’t. I needed to know.

“It’s a luck charm, boy,” he called, after a pause, his voice gentler, sympathizing. “It brings you luck alright, for a number of years… and then…and then it takes back all it gave. You can’t give it away. You can’t throw it away. You can’t lose it. You can’t sell it. And when it’s tired of luck, that’s when it all begins… the nightmares.”

*******************

One…

So here I was. I’d had a good forty years. Adventuring in the wildest corners of the world, playing with my fortune, stealing gold from a dead smuggler’s large brown leather case and trying out my version of the perfect murder at the same time, exploring the depths of the remotest jungles on the earth, hunting scary wild beasts, trying my luck to the farthest stretch. And now… well, luck was a funny thing. It gave and it took. What it had given me was a wild crazy life of my fancified desires. What it had taken away was the ability to get around without luck. I mean, so many unlucky people seem to get around fine without it. But now that I’d got used to it, I couldn’t imagine a life without luck. So I was done for. Finished. Dead. And dead unlucky, at that.

The crazy car, the stupid birds and the sick man – they had just been the beginning. It got so much worse after that. From near-death accidents, no less than five broken body parts, one dead friend and two dead parakeets to huge gambling loses, stock-market crashes and a short-circuit fire that blew up my beautiful New York apartment, I’d experienced it all, what an old man from my shady past had called “the nightmares”. And I guess I could have stood through all that… if it wasn’t for the real nightmares. The woman in the car: the pretty lady I’d seen the day it all began. Every night I dreamt of her. Just staring at me throughout every scene of my dreams. Her cold gray mocking eyes locking into mine, triumphant and evil. I woke up in a cold sweat every morning, that frightening beautiful face haunting my thoughts and my very consciousness. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I didn’t know who she was, or why she frightened me so. I just couldn’t take it.

I tried throwing the amulet into the river. It got caught on the suspension wires of the bridge. I tried leaving it there, and every place I went to, every restaurant I ate at. It kept reappearing in my coat-pocket. So in the end I thought maybe I should end this thing. Really end it. And what better place to end it than the place it had all started in. The music hall that had been built, a year after I left, over the meadow the circus had parked itself in. It was in disuse now. Broken-down, neglected, forgotten. Like the life that I’d left for a more exciting one. And this was the end…

Zero…

The light bulb hanging by the door flickered and died out.

**************************

Stop. Rewind there a bit. What had I said back there? “So many unlucky people seem to get around fine without luck.” And what had the circus people done? They’d traded their fortune for mine, losing the amulet to me. How had they done that? One last spurt of luck before the dark? I didn’t think so. The amulet was, before all, a luck charm. And losing it, then, wasn’t lucky at all. It was unlucky. “The amulet takes back all the luck it gave.” And the first bout of luck was finding it in the first place. But you couldn’t lose the amulet. You couldn’t give it away, throw it away or sell it. But the circus people hadn’t given it to me. They hadn’t lost it, or sold it. I had taken it from them. Stolen it. “Voluntarily.” So maybe the way they got around fine without the amulet’s luck was because they were unlucky. Unlucky enough to have it stolen from them. So maybe… maybe it wasn’t too late for me. I lowered the gun.

I heaved myself into the overcrowded bus. The signs glared down at me from above every dark head: “Beware of Pickpockets”. I’d figured the best way to lose it was the Thomson and Thompson way: the end of a chain of pure silver that I’d attached to the amulet hung from my coat-pocket, swaying with each jolt of the wheels on the potholed road, temptingly. A poverty-stricken country in the hotter regions of the world. Faces, brown from continuous exposure to the tropical sun, stared curiously at me, an out-of-place visitor, reeking of wealth. It was a bus that carried farmers from the market to their villages miles and miles away, farmers, travellers, traders and the odd pickpocket or two. So why did I prefer these pickpockets to our own back at home? Simple, I wanted that amulet as far away from me as possible. And as far away from the places I was likely to go to in the near future. Assuming I’d escape the enchantment, of course.

I moved in to the centre of the narrow passage between the seats. There was no room to sit, and I guess I preferred it that way. I wanted to attract all the attention I possibly could. Correction, I wanted the chain in my coat-pocket to attract all the attention it possibly could. And I waited. Waited for that heavenly soft tug on my coat that I’d hardly notice if I hadn’t been waiting for it, wistfully. One hour. Two hours. Three. And it never came.

The bus was out of the town area, speeding through fields of yellow corn, wilting under the heartless sun of the drought season. The roads were worse here, the bus hardly inching its way in and out through mounds of abandoned ‘repair work’ that had started last century and would end the next millennium. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky or a drop of water on the dry earth. We neared a village and the bus stopped, the conductor leaning out to help the new passenger in.

My heart skipped a beat. I stared, dumbfounded into the eyes of the woman from my nightmares – the woman in the car that dreaded day – the woman who frightened me so much that I would have driven myself to suicide. Only her gray eyes had lost their cold malevolence. They were friendly and surprised, finding another American in this place. She came walking up to me and stood next to me.

“Tourist?” She asked. Her presence didn’t frighten me as it always did, her face didn’t scare me.

“Yes. I’ve seen you before, back at home.”

A look of panic flashed through her eyes – so fast that I almost didn’t notice. “I… think you must be mistaken. I haven’t been in America for ages.”

Then I remembered where I’d seen her. Before that day on my way home from the coffee shop, of course. Her face had looked familiar then. Now I knew why. She was the woman who had been suspect in the Manhattan murder cases in ’98. I seen her on the front of the Daily and forgotten her, along with thousands of New Yorkers that year.

She must have seen the fleeting look of recognition in my eyes. She turned and pulled on the emergency chain. The bus braked, with a sudden jolt that sent me lurching forward, grabbing wildly onto the nearest seat. When I’d recovered and stood up, she was gone.

I put my hand instinctively into my coat-pocket. The amulet was gone, too. With her… and away. I knew it was gone, now. Finally. Forever. She’d never come back to America. Or here, for that matter. For the same reason why I never cross the Atlantic on boats anymore. And I… I was free.

It had been a good thing after all, meeting her here in one bus out of a dozen, in one town out of scores, in one country among hundreds – a chance in a million. Lucky.

Or should I say unlucky?

****************************